Syrians were mainly merchants, but when they first arrived, they peddled. Peddling required little capital (they were given goods on credit), little English, and the peddler was self-employed. Syrians divided peddlers into two types: kesha (notions) peddlers and jezdan harir (silk bag) peddlers. Kesha included small dry goods like razors, celluloid collar stays, detachable collars and cuffs, needle and thread, kitchen towels, and shoelaces as well as some Holy Land trinkets, such as rosaries. Women keshahi carried lace collars and cuffs, sewing supplies, cheap jewelry, scent and soap, and Holy Land trinkets. One step up the economic ladder were the jezdan harir peddlers who carried fancy or Turkish goods, such as embroideries, damask cloths, tapestries, lacework, and small exotic items like damascened daggers. Stopping at resort hotels around New York State, "Ladies of the Road" sold fancy goods to other hotel guests. Day peddlers went door-to-door in an upscale part of the city and came home at night, but long-distance peddlers would leave the city for weeks at a time, carrying what they could and picking up new stock from their New York supplier at a local railway depot.

Sign of D.J. Faour and Brothers' store, 63 Washington Street.

Work

The classic story of the Syrian immigrant has him (it was nearly always a male in the story) going from penniless peddler to wealthy capitalist. Like all myths, this one carries elements of truth and much embroidery. The majority of new immigrants, including many women, did start out as peddlers, but others worked in factories or mills around the Northeast. Peddlers sold notions, dry goods, small textiles, cutlery--anything that could be carried in a bag or basket from house to house. Although dependent on their Syrian suppliers for credit, goods, routes, and sometimes even the homes they lived in, peddlers were self-employed and their profits largely a result of their efforts and skill.

The Syrians who eventually became merchants first started out as peddlers. Women usually retired from peddling when they married and began to raise a family, but some continued to work, either running a small shop or working in a factory.

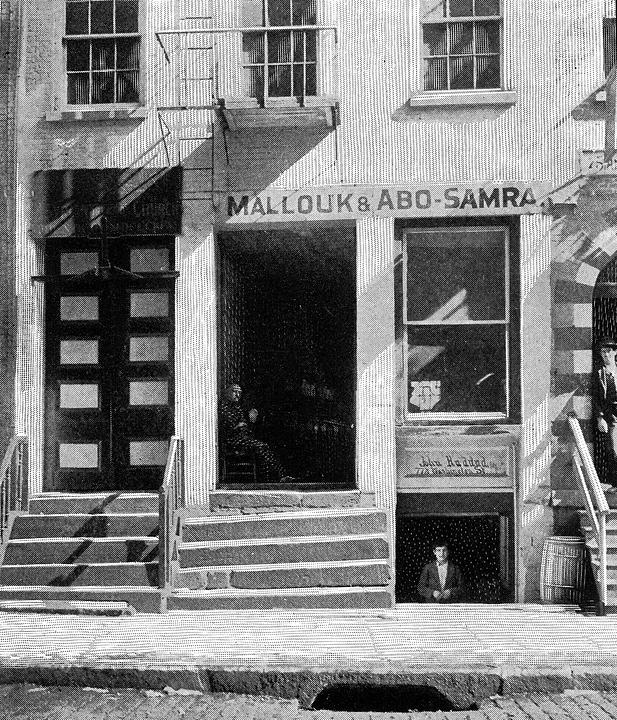

A man might open a small retail shop or become a supplier, wholesaler, or importer/exporter of dry goods, textiles, groceries, or Turkish or religious goods. Some opened small factories for cotton goods; others manufactured cigarettes, mirrors, brushes, and suspenders. Not everyone was a merchant: doctors and pharmacists, bankers, restaurant owners, newspapermen, as well as poets, writers, and musicians all lived and worked in the colony.

The Syrians who eventually became merchants first started out as peddlers. Women usually retired from peddling when they married and began to raise a family, but some continued to work, either running a small shop or working in a factory.

A man might open a small retail shop or become a supplier, wholesaler, or importer/exporter of dry goods, textiles, groceries, or Turkish or religious goods. Some opened small factories for cotton goods; others manufactured cigarettes, mirrors, brushes, and suspenders. Not everyone was a merchant: doctors and pharmacists, bankers, restaurant owners, newspapermen, as well as poets, writers, and musicians all lived and worked in the colony.

The men who became suppliers often carried on selling the same items they had peddled but at a larger scale, supplying not only Syrian peddlers but also retailers around the city. Import-export merchants used a worldwide network of Syrian contacts to import linens and Turkish goods from the Middle East and Europe and export American goods to South America, the Caribbean or back to Europe. At the five-story building at 60-62 Washington Street, Syrian workshops turned out cotton dress goods, including the cotton kimonos worn by millions of women as dressing gowns, as well as suspenders, cigarettes, and brushes.

Less ambitious men would open small retail shops that catered mainly to other Syrians: groceries, barber shops, pool halls, boarding houses, and restaurants.

There was no shortage of professionals even in the earliest days of the colony. A half-dozen doctors, a like number of pharmacists, and three midwives took care of most of the community's health needs. The first Arab bank, opened by George Forzly in 1897, went under only two years later, but the second bank, Faour's, at 81-85 Washington Street, lasted from 1906 until the Depression.

Many who were fluent in English made a living by lecturing at churches, YMCAs and concert halls around the country. A man with a literary bent might publish a newspaper, print books that were sold by subscription, and do commercial printing to shore up the bottom line. A half-dozen doctors, many with medical degrees from the then-named Syrian Protestant College, practiced medicine in the community.

Less ambitious men would open small retail shops that catered mainly to other Syrians: groceries, barber shops, pool halls, boarding houses, and restaurants.

There was no shortage of professionals even in the earliest days of the colony. A half-dozen doctors, a like number of pharmacists, and three midwives took care of most of the community's health needs. The first Arab bank, opened by George Forzly in 1897, went under only two years later, but the second bank, Faour's, at 81-85 Washington Street, lasted from 1906 until the Depression.

Many who were fluent in English made a living by lecturing at churches, YMCAs and concert halls around the country. A man with a literary bent might publish a newspaper, print books that were sold by subscription, and do commercial printing to shore up the bottom line. A half-dozen doctors, many with medical degrees from the then-named Syrian Protestant College, practiced medicine in the community.

Featured

Get started with these points of interest

..jpg?locale=en)